Hyperglycaemia Induced Hyponatraemia

Overview

In hyperglycaemia, plasma Na+ falls (hyponatraemia) because the increased osmotic load of elevated blood glucose draws fluids from the intracellular compartments of the body into the blood. This is dilutional hyponatreamia - just one of many causes of plasma Na+ abnormalities. It is possible to calculate how plasma Na+ will be restored in hyperglycaemia after plasma glucose levels are restored with the administration of insulin, which can aid successful management of patients. How the body is able to dilute blood in this way, in the face of osmotic diuresis and continual fluid loss in hyperglycaemia is an apparent paradox that provides an opportunity to think about fluid and solute homeostasis.

Dilutional hyponatreamia

In diabetic hyperglycaemia, the lack of insulin not only increases blood glucose, but it inhibits processes that allow cells to take up glucose, so we can think of cells as being impermeable to glucose. Under these circumstances, when blood and the tissues of the body meet, simple osmosis shifts water from inside cells into the blood down the osmotic gradient towards glucose. This has the effect of diluting all the solutes in blood down, most noticeably Na+ since it is the major cation in blood. This is dilutional hyponatraemia. The body hasn’t actually lost any sodium in this process, it has just become more dilute in blood. In fact you can calculate what the concentration of Na+ should be if you took away the excess glucose. This is well worth doing, because administering insulin to a patient with hyperglycaemia will do precisely that: glucose will drop, its osmotic effect will vanish and water will return to tissues “undiluting” plasma Na+.

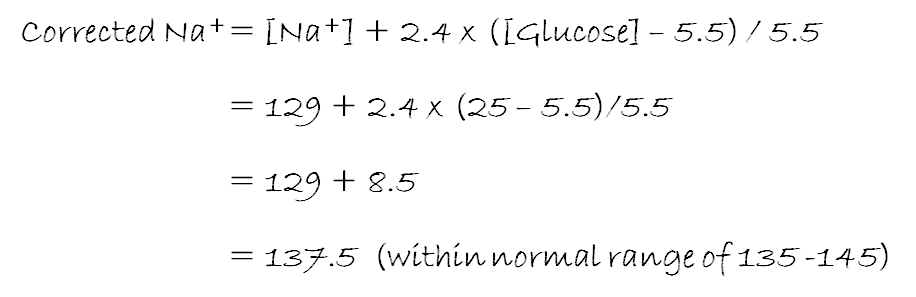

This equation uses concentrations in mmol/L; there are similar ones when the glucose concentration is known in mg/dL instead. All are based on, or modifications of, Katz, MA. (1973) Hyperglycemia-induced hyponatremia - calculation of expected serum sodium depression. N Engl J Med. 289(16):843-4.

Say we had a hyperglycaemic patient with [Na+] = 129 mmol/L and [glucose] = 25 mmol/L. With [Na+] <135 they are hyponatraemic, but what would happen if we lowered their blood glucose level to normal?

Although we use the term “corrected” here, this patient is hyponatraemic until the glucose is corrected by insulin, in which case we expect the Na+ concentration to rise back to our calculated 136.8 mmol/L. So long as excess glucose is present in blood making it hypertonic, plasma will continue to siphon fluid from the tissues by osmosis, diluting sodium in the process.

How does a dehydrated patient with polyuria manage to find some “spare” water to dilute hypertonic blood?

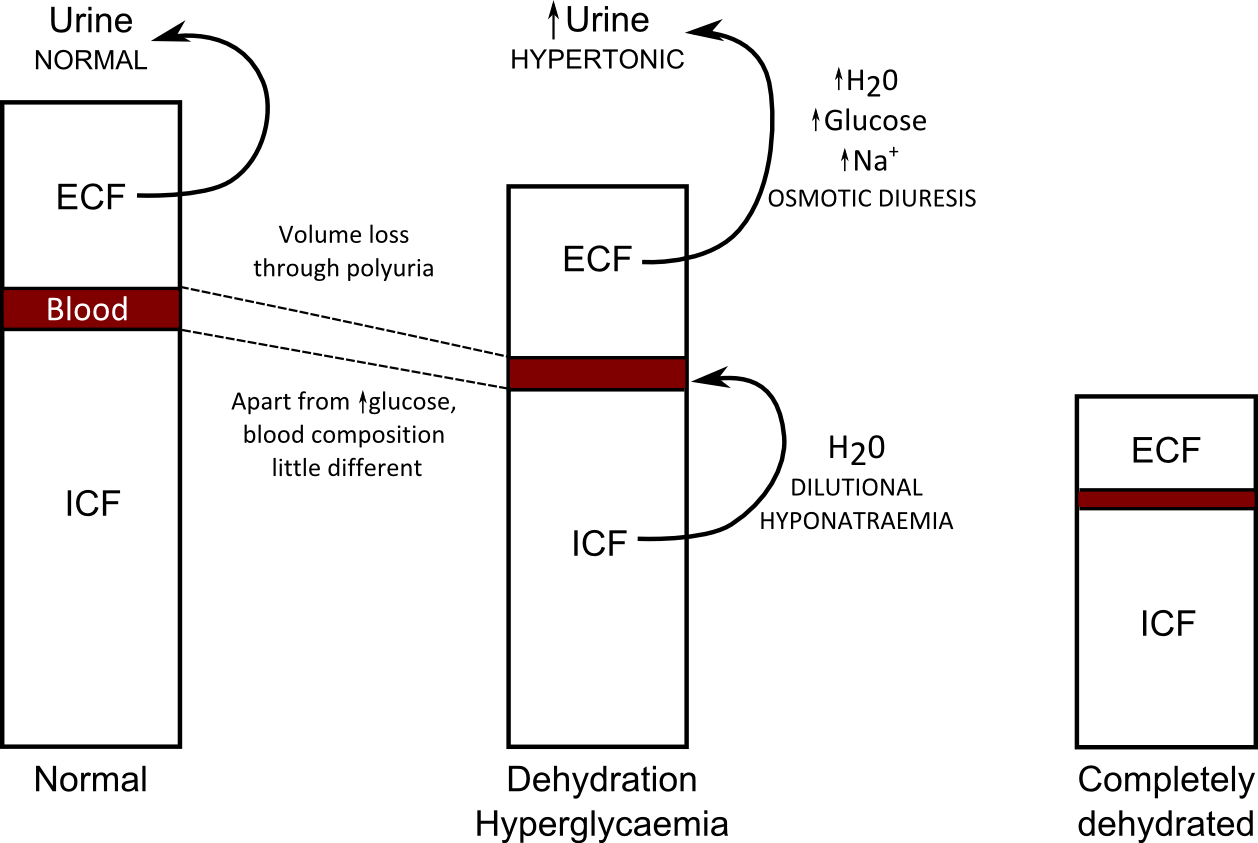

If a hyperglycaemic patient’s plasma Na+ is not looking too hyponatraemic, they’ve probably lost so much water that dilutional hypernatreamia is no longer possible. There’s a hint there: if you lose too much fluid you can’t become hypnonatreamic; patients with the worst volume depletion have better plasma Na+ . Until that point is reached there is some fluid buffering capacity in the body (Figure 1). Remember dehydration is a relative term, not an absolute. You can be slightly dehydrated, or very dehydrated.

The key points here are:

- Polyuria in diabetes is due to the osmotic effect of glucose on reabsorption of fluids and solutes by the kidney: osmotic diuresis

- The loss of fluid and solutes is effectively plasma loss and the plasma glucose continues to remain elevated, making plasma hypertonic.

- The hypertonicity of blood draws fluid from the ICF in cells. This restores plasma osmolality but dilutes sodium down leading to hyponatraemia (see above).

- Essentially, the ICF tops up plasma with fluid which is then lost in urine until fluid loss is such that blood and the ICF are isosmotic. This is life-threatening dehydration.